The African-American 371st Infantry Regiment

They were southern draftees sent into the bloody trenches of World War I. They came out as heroes – having earned numerous individual awards for bravery including the Distinguished Service Cross, Croix de Guerre, Legion of Honor, Médaille Militaire, and a Congressional Medal of Honor.

The 371st Infantry Regiment (Colored) was formed in August 1917 and consisted of African-American draftees, mostly from South Carolina, with additional members from Florida, Georgia, North Carolina, other southern states, and elsewhere, including Maryland and Pennsylvania. They were commanded by white officers, mainly from the South.

After training at Camp Jackson, where it was deemed the best-drilled unit, the Regiment arrived on the Western Front in April 1918. It was placed under the command of the French Army because of their desperate need for new troops, and the feeling that the French could better integrate these black soldiers.

After training in the new French equipment and tactics, on 12 June 1918, the 371st went into the trenches as part of the veteran 157th “Red Hand” division. The 371st remained in the line for over three months, holding first the Avocourt and later the Verrières subsectors northwest of Verdun.

The regiment was then taken out of the line and thrown into the great September 1918 offensive in the Champagne. It took Côte 188, Bussy Ferme, Ardeuil, Montfauxelles, and Trieres Ferme near Monthois.

The regiment captured many German prisoners, 47 machine guns, 8 trench engines, three 77mm. field pieces, a munitions depot, many railroad cars, and enormous quantities of lumber, hay and other supplies.

It shot down three German airplanes by rifle and machine-gun fire during the advance. During the fighting between 28 September and 6 October 1918 its losses, which were mostly in the first three days, were 1,065 out of 2,384 actually engaged. The regiment was one of the most forward units of the attacking army in this great battle.

““The percentage of both dead and wounded among the officers was rather greater than among the enlisted men. Realizing their great responsibilities, the wounded officers continued to lead their men until they dropped from exhaustion and lack of blood. The men were devoted to their leaders and, as a result stood up against-a most grueling fire, bringing the regiment its well-deserved fame.”

American Negro in the World War

““I am sorry if I neglected to tell you that the 371st is a ‘Colored’ Regiment for I am certainly not ashamed of the

fact and doubt if we have an officer that is.”

Battalion 371st Infantry Regiment

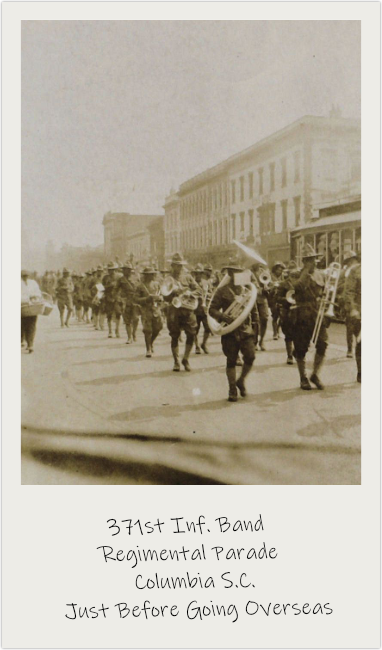

The Return to Columbia

Upon its return from France, Columbia came together in support of the 371st. A mass meeting was held at Sidney Park Church to launch a fundraising effort for a community reception at Allen University in honor of the 371st. The grand event was held on February 29, 1919. SC Governor Robert Archer Cooper and African American community leaders, including I.S. Leevy and C.A. Johnson, spoke in honor of the regiment.

“This historic city has set a fine example for other cities in the south in its interest in the return of the soldiers of the 371st Infantry from France. …Thousands of both races turned out to see the parade, these soldiers being the first to return in a body, having seen actual fighting. The white people dropped the color line and not only viewed the parade but joined the shouting and crying for joy.”

The two flags of the 371st Regiment were presented to the community.

One of the flags was a hand painted silk flag, presented by the black citizens of Columbia before the 371st departed for France.

The other, is an official US Army issue embroidered flag.

These flags are now part of the flag collection of the South Carolina Confederate Relic Room and Military Museum.